India, the most populous nation in the world, is planning to include caste information in its upcoming census, a decision that is expected to have far-reaching socioeconomic and political effects. When Ashwini Vaishnaw, the minister of information, declared on Wednesday that the census would include caste data, he did not specify when it would start. The decision, he claimed, showed New Delhi's dedication to the "values and interests of the society and country."

The count is expected to spark calls to increase the nation's quotas that reserve elected office, government employment, and college admissions for specific castes, particularly for a large portion of the lower and intermediate castes known as Other Backward Classes. According to India's current policy, OBCs are entitled to 27% of the quota, which is limited to 50%.

So, What is Caste?

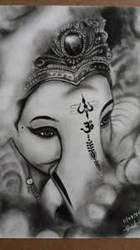

In India, caste is an old social hierarchy that plays a vital role in both politics and daily life. There are hundreds of caste groups in India, especially among Hindus, according to economic status and occupation, but the number of members of these groups is either unreliable or out of date. The caste system in India, which has its origins in Hindu texts, has traditionally divided people into groups according to their birth families, defining their jobs, places of residence, and potential spouses. Many non-Hindu groups in India today, such as Christians, Muslims, Jains, and Buddhists, also identify with particular castes.

From the top Brahmins, who were traditionally priests or scholars, to the Dalits, who were once referred to as the "untouchables," who were forced to work as waste pickers and cleaners, there are thousands of sub-castes in addition to the main castes. Dalits and other marginalized indigenous Indians were viewed as "impure" for centuries, making them the lowest castes. They were sometimes even prohibited from entering the temples or homes of the upper castes, and they were made to eat and drink in communal areas using different utensils.

Why now?

Modi has long opposed efforts to categorize people along traditional caste lines, saying that the poor, young people, women, and farmers were the four "biggest castes" and that improving their lot would benefit the development of the entire nation. However, growing dissatisfaction among disadvantaged castes helped opposition parties in the 2024 national election, which produced a shocking outcome: despite Modi winning a third term, the BJP was unable to secure a majority in parliament, which reduced their influence.

His opponents argue that Modi's reversal on the caste census is a political ploy to boost support ahead of the next state elections, especially in Bihar, a battleground state where the topic has been especially delicate.

“The timing is no coincidence,” wrote M. K. Stalin, the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu state and a longtime Modi critic, in a post on X. “This sudden move reeks of political expediency.”

The federal government claimed in a statement that the surveys conducted by a number of other states were "varied in transparency and intent, with some conducted purely from a political angle, creating doubts in society."

The government's announcement was hailed by the main opposition Congress party, which said Modi had given in to their pressure. Meanwhile, BJP leaders claim that the opposition politicized the caste issue for their own benefit after failing to carry out a caste census during their years in power.

A national caste survey was carried out in 2011 by the previous Congress-led government, but the results were never released in full. Critics claimed that the partial results revealed methodology problems and data anomalies. Additionally, it was distinct from the national census that year, so it is impossible to compare the two sets of data.

A Controversial Proposal

Not everyone supports the caste census.

Critics contend that rather than formalizing these labels, the country should be working to move away from them. According to Desai, a professor of applied economics at the National Council of Applied Economic Research in New Delhi, some people think that government programs like affirmative action should be based on socioeconomic class rather than caste.

Another factor is that the government might increase the amount of affirmative action given to marginalized castes if the census shows that they are larger than previously believed, as was the case in Bihar. This would enrage some traditionally privileged castes that already detest the quota system.

Instead of depending on out-of-date data, the census could clearly show who needs what kind of help and how to best deliver it, Muttreja said. Intersectional gaps may be revealed; for example, a woman in rural India may face greater challenges than a peer in an urban area or a man of the same caste. It might also reveal whether any castes have grown so large that they are requesting more money than is currently available.

No comments yet.